From the Dining Room to the Board Room, Investments in Care are Overdue

Earlier this week, I wrote about how U.S. women’s soccer is undergoing a radical transformation—all thanks to players who refused to see their work so undervalued, and underpaid, any longer. (The agreement was finalized today!)

Just as women's sports have been undervalued (despite women's cultural and financial contributions), so has paid and unpaid domestic work. “Women’s issues” are commonly considered losing issues in politics and as investment strategies, even though they are often synonymous with community issues that impact everyone.

There is a cost to NOT investing in women

The lack of investment in women across the board, including as founders, in women’s health, and in issues like the care economy, has silent but disastrous costs. Economists have started to evaluate and quantify the extent to which women and minorities have been harmed by not being in (or honestly, even near) the technology “rooms where it happens,” starting with underrepresentation among startup founders, patent inventors, and venture capitalists.

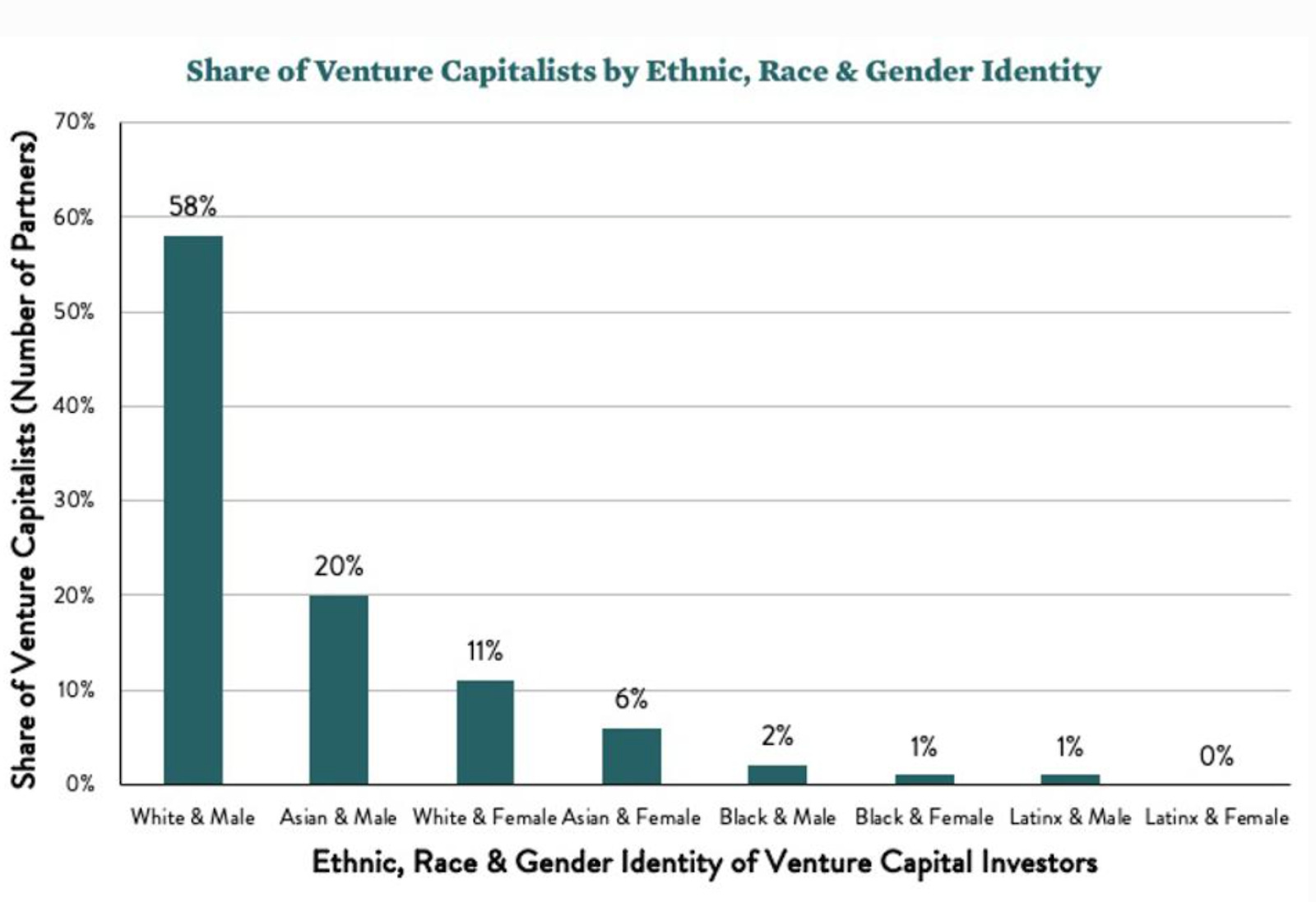

Care economy workers (often women of color), women working double-shifts, and homemakers are unlikely to be “in the room” where investment decisions are made. This means that when evaluating the true need for startups that support household care, it is unlikely anyone making that decision will have personal experiences of the true cost that work entails. Looking at investment data from venture capitalists, we can see care issues are not yet prioritized. According to The Information, despite a few years of significant gains for women as partners in these firms, women still hold only 22% of capital decision-making roles. To be brutally honest about this: that’s Asian and white women. Black and Latina women make up about 1% of that number.

In terms of capital raised, Pitchbook reports that since 2008, at best, 16% of capital raised in a financial quarter went to startups with at least 1 female founder. For leadership teams consisting of female founders only, the percentage of capital has remained stagnant at just over 2%.

“When we invest in women and girls, we are investing in the people who invest in everyone else.”

-Melinda Gates, 2014

Investing in women is good for communities.

Economists Einio, Feng, and Jaravel noted, “We find that equalizing access to innovation could substantially reduce inequality and increase real income growth at the median of the income distribution. …transitioning from the current distribution of innovators’ backgrounds to an ‘equal opportunity’ innovator pool would lead to much larger welfare gains for lower-income households. Furthermore, we find that the gender gap in innovation strengthens the gender ‘real wage’ gap through the direction of innovation.” Putting a metric with this, they added, “a female-led startup generates welfare gains for female consumers that are 27% larger than for male consumers.”

In other words, flipping the tables—and leveling the playing field for investment and innovation—means benefits for women across the board. It’s past time for equal investment, starting with a greater representation for issues regarding our care economy.

Applying business economics to the care economy

The U.S. women’s soccer team’s win against the U.S. Soccer Federation is a terrific example of how much power the court of public opinion has. Now it’s time to leverage that power to change the landscape of the care economy. When considering a social challenge, leveraging double-sided networks to solve such a widespread pain point seems as obvious as pay equity for women’s soccer players, and it has been as elusive. Some of the first and largest double-sided networks focused on gaming (Valve, 1996), building social networks (Facebook, 2004), cheap travel (Airbnb, 2008), splitting bills (Venmo, 2009), and getting around in the city (Uber, 2009). These are all issues that impact society as a whole, but in particular, young men. And it’s no wonder that men over-index as workers in these companies as well.

To date, investments in technology platforms that value the care economy have been limited, and those that have attempted to disrupt the space report low and mixed results. One of the most challenging aspects of disrupting the care economy is the painful truth that care is not where the money is. It is an economy that values cheap labor over premium experiences.

To overcome short-sided market definitions of value, care-based startups will need to take a page from the playbooks of companies that have changed and revalued the way we think about products or services. Starbucks is an example we’re all familiar with: Howard Schultz reintroduced Americans to coffee by making it an experience and fundamentally redefined coffee’s acceptable price point in the process. Technology platforms provide an opportunity to do something similar for the care economy.

The court of public sentiment can do better. We define what we value.

Up to this point, these technology solutions have treated the care industry as a low-value economy and worked to provide services at bottom-dollar pricing while stretching those paltry dollars. A few that have experienced moderate success are childcare services (Care.com, 2006) and, more recently, kid transportation (HopSkipDrive, 2015).

A few other technology solutions have tried and failed in the care economy. Homejoy was a San Francisco-based home cleaning service that I used and loved. They connected home cleaners with an alternative way to schedule cleaning appointments, leveraging the gig economy to provide home cleaning services. When they closed in 2017, they cited the changes in employment laws in California that re-classified gig workers like theirs as employees, making their business model untenable. It appears that even before this announcement, the company may not have been solvent. Unfortunately, even on a large scale cleaning services are often compensated at minimum wage or less(!) in the market. Homejoy couldn’t compete when their prices were undercut and they couldn’t sustain growth—or offer fair wages—with a service that was so fundamentally undervalued. For Homejoy, starting at the bottom of the market and hoping to find profit at scale failed.

It makes me wonder what would happen if, rather than trying to offer the services for the cheapest amount possible, the care economy started with premium experiences and looked at how to disrupt the market from a position of wealth and deeper commitment to the value of those experiences. For all of these care companies, there is agreement that they are solving major pain points—and these are social challenges that should be ripe for technology to disrupt with the opportunity to solve some of our most meaningful social issues.

NPR recently aired an interview with Angela Garbes, who points out, “Most domestic laborers and childcare providers are women of color, and they are mothers. And so who's taking care of their children? You know, childcare workers are three times more likely to live in poverty than any other worker, which is really a shameful statistic. [... it is on each member of society to find] solidarity with the people who do care work for us and [say] these people deserve a living wage and these people deserve basic worker protections.”

Break the vicious cycle

When women are not in the position to invest in the issues that most impact them, when women’s companies do not receive investment, and women are not engineering the next wave of technology, it’s little surprise that our systems of finance and innovation make it difficult to ease the second-shift struggle most working mothers experience and reduce the cognitive and physical load of homemaking. It’s even less surprising that our systems don’t fairly compensate the people who do work to ease that load.

As we've seen from women’s soccer, changes in public sentiment can lead to sweeping changes in how women's work is compensated; now, it's time to take these same tactics into spheres that typically get less attention.

There are dozens of things you can do right now to flip the script. Here are just a few ideas:

- Recognize the work done at home is just that: work. If you can afford home support, give yourself back some time and release the guilt to do it all.

- When determining payment for home support, consider the estimated livable wage in your area.

- Support the National Domestic Workers Alliance.

- Learn about Gender Lens Investing.

- Use the Gender Smart ecosystem to evaluate investment impact.

- Join the 2X collaborative or seek out other gender investment strategies.

I want to hear about the strategies you’ve tried to rewrite the way women’s contributions to society are valued. As a female founder in a company that is largely staffed by women and is in the care economy, a historically unvalued and gendered field, I am also actively looking for introductory meetings with individuals who would like to invest in women as a part of their impact investment portfolio. Reset Your Nest isn’t taking money yet, so now is the perfect time for early introductions. Please, let me know if you would like to chat and learn more about Reset Your Nest growth plans or if you know someone who would!